Minnesota Department of Health

Research in Action (RIA) partnered with members of the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) to conduct a landscape assessment on barriers to Black and Indigenous populations accessing and using medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs). With this landscape assessment, MDH hopes to directly address community-identified barriers and identify intervention points for future work on MOUD use and access.

PARTNERS

The Minnesota Department of Health Overdose Prevention Unit and the Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Prevention and Control Division monitors the occurrence of infectious diseases, develops strategies for preventing and controlling disease, and works to put those strategies into action. Learn more here.

PROBLEM

Opioid overdose deaths disproportionately impact Black and Indigenous communities. In 2021, Indigenous Minnesotans were ten times as likely and Black Minnesotans were three times as likely to die from opioid overdose than their white counterparts. These deaths are preventable: research shows that medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs) are effective treatment options that reduce overall opioid use and prevent overdose. These medications reduce opioid cravings and manage withdrawal symptoms. There are currently three MOUDs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

But, while medical professionals often view MOUDs as a key ingredient to successful opioid use treatment, Black patients receive MOUDs in emergency and inpatient environments at nearly half the rate of white patients nationally. Black community members are also significantly less likely than their white counterparts to receive MOUDs from physicians or pharmacies. While buprenorphine use has generally increased over the last two decades, increases in use and access are greater in higher-income white neighborhoods than in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of Black residents.

Compared to other states, Minnesota’s policies facilitate greater MOUD access, such as not imposing stringent eligibility requirements on patients for take-home doses. However, disparities in access for Black and Indigenous communities suggest that additional investigations are needed to eliminate barriers to MOUDs. Scholars have called for research that centers on input from those with lived experience, which would help uncover barriers and generate strategies to improve access. This project answers the call by examining the intersections of race and related factors and patient narratives to identify barriers and solutions.

PROCESS

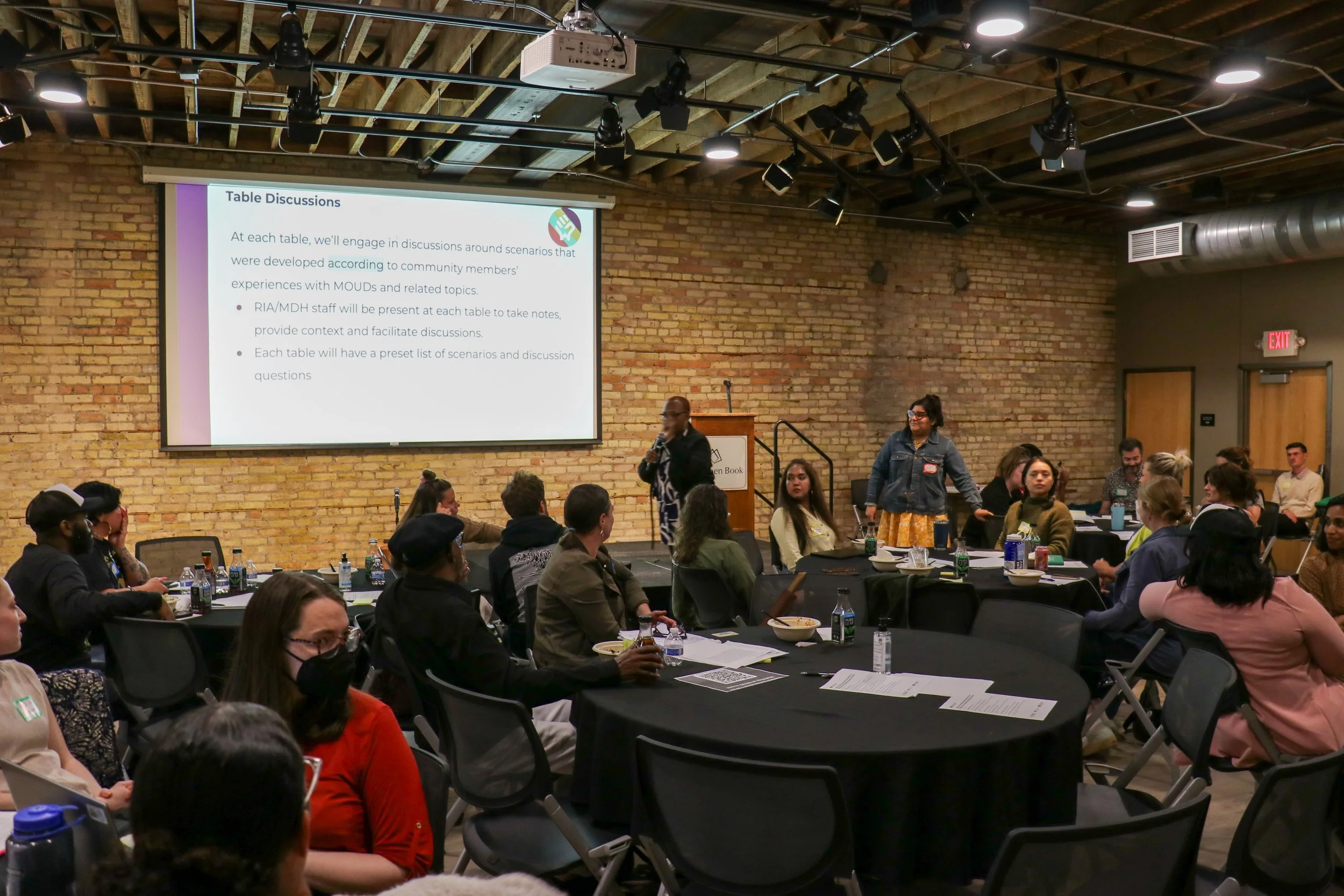

The MDH project team connected us with recovery community organizations (RCOs) and syringe service programs (SSPs) that either received grants from MDH for SSP operations or were otherwise professionally connected to members of the MDH project team, most of whom were based in the Twin Cities metro area. To collect data and insight we conducted interviews with 20 Black and Indigenous community members, as well as five members of RCOs and one counselor from an MOUD clinic.

Recommendations

-

Community members had to navigate difficult circumstances surrounding the regulation of MOUDs and restrictive treatment practices. Reduced restrictions around methadone in response to the COVID-19 pandemic increased patient access to their treatment, reduced their exposure to stigmatizing social situations, and bolstered the agency they had over their treatment. While buprenorphine medications are less regulated than methadone, community members still reported restrictive practices around the medications’ availability that suggest this class of medications, in general, is not made fully accessible to patients.

-

Community members stated that providers often are not understanding of their circumstances and are not equipped to meet them where they are in their journeys. However, community members’ positive treatment experiences stemmed from providers’ compassion, investment, and efforts to structure a treatment plan that truly works for a patient’s goals. Previous work on patient empowerment and success suggest that patient-directed care, even in highly-regulated methadone treatment contexts, is possible and leads to increased retention and better treatment outcomes. Treatments are also likely to be more accessible and supportive of community members when providers implement multidisciplinary, coordinated care efforts rather than a single physician coordinating all aspects of a patient’s treatment.

-

Community members were primarily in favor of mobile MOUD options beyond the walls of traditional healthcare settings. Mobile clinics would disrupt common barriers by bringing necessary care to more accessible community sites, where people frequently gather or congregate. Mobile clinics would be particularly beneficial in reaching unhoused communities and those with limited access to transportation. Expanding MOUD access via mobile clinics would also require providers’ more direct participation in community health promotion outside of the walls of a clinic or hospital. Mobile clinics often rely on volunteer hours from physicians and other staff. Organizations cannot explore the viability of implementing a mobile clinic without express willingness from providers to engage in more progressive community health solutions that disrupt inequitable barriers. Previous assessments of mobile MOUD access suggest that they are a viable strategy to engage different community members in treatment while overcoming specific barriers like stigmatizing healthcare environments and limited clinic locations.,

-

Community members’ variable experiences with healthcare providers and MOUDs highlight the need for a standardized and rigorous curriculum on MOUDs to ensure that providers are safely coaching their patients through their entire treatment. Providers often cannot correctly distinguish between different MOUD mechanisms, and lower levels of knowledge on MOUDs are associated with greater stigmatized attitudes toward patients who use opioids. This pattern suggests that a more holistic education on MOUDs for providers may address prevailing forms of stigma. Educational resources on MOUDs, rather than reiterating standard medical jargon, should uplift the realities of those with lived experience on these medications so that providers have greater context. These educational resources should also uplift treatment strategies recommended by those with lived experience such as incorporating cannabis, which can help patients navigate negative symptoms and potentially boost MOUD treatment retention.

-

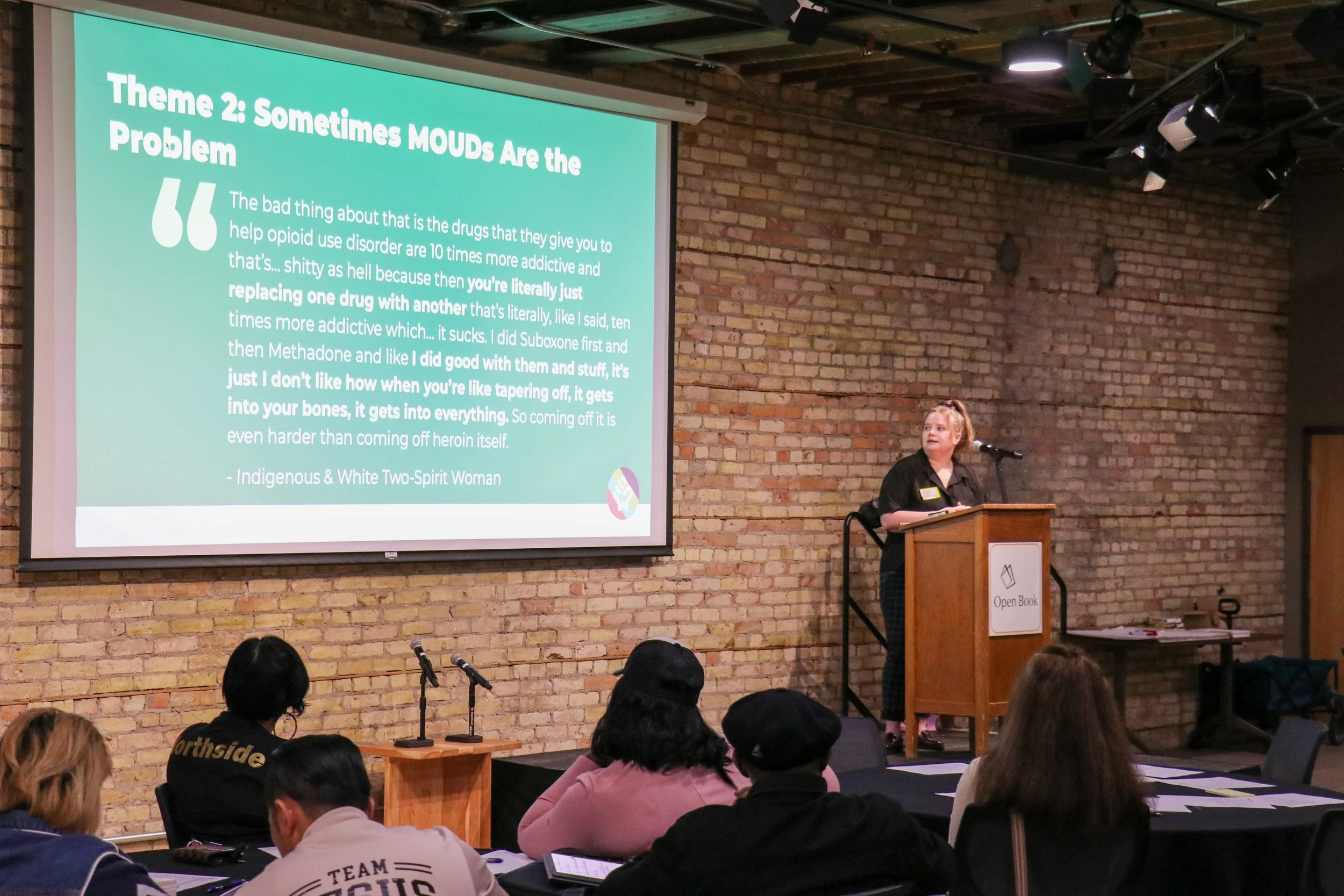

Community members are still navigating internal and external stigma around MOUDs. This stigma can affect people’s willingness to engage with MOUDs as a viable treatment option and their desire to continue long-term MOUD use. Both providers and community members who use opioids can stigmatize MOUDs as an indication that one isn’t actually in recovery, in addition to the belief that MOUDs should only be used as a temporary tool., These restrictive representations of recovery obscure the individualized nature of recovery as well as de-emphasize the reality that some rely on MOUDs as a tool to support their long-term well-being, like many other medications for chronic health conditions.

-

Community members and informants closest to the topic at hand shared extensive wisdom and insight on what is contributing to use and access barriers for Black and Indigenous clients. However, we have only scratched the surface of community insights and community-identified solutions to enact actual systemic change. We recommend building on the learnings from this landscape assessment to implement a larger-scale project, where we can further implement our Equity in Action model to identify prevailing barriers and proposed solutions from Black and Indigenous community members.